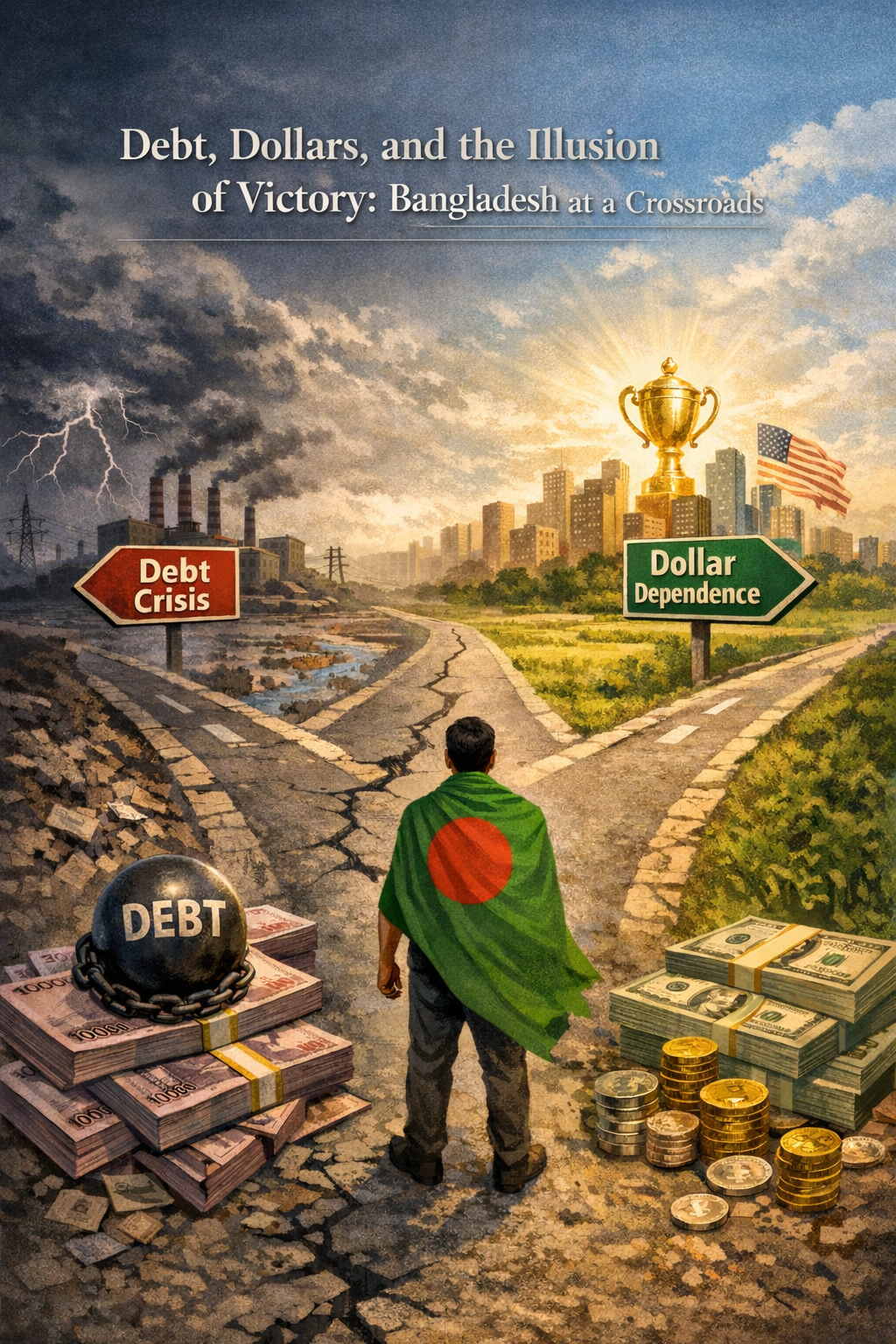

Debt, Dollars, and the Illusion of Victory: Bangladesh at a Crossroads

Prof. Dr. Arif:

The International Monetary Fund’s sudden release of $1.3 billion—part of the long-delayed fourth tranche of its loan program—has been presented by some as a policy breakthrough. Yet the disbursement, reportedly suspended since August 2024 after repeated failures to meet reserve and reform conditions, raises deeper structural questions. Meeting the IMF’s benchmarks—maintaining a usable reserve balance of $15.3 billion, expanding taxation, and cutting subsidies—may satisfy external auditors. But whether it strengthens the domestic economy is another matter entirely.

The Yunus-led administration has reportedly accumulated nearly $12 billion in additional foreign debt, alongside approximately 60,000 crore taka annually in domestic borrowing over the past two fiscal years—roughly $14 billion raised from local banks. Yet there has been no visible surge in infrastructure modernization, industrial mega-projects, or large-scale employment initiatives. Debt that does not translate into productive capital formation risks becoming a short-term stabilizer rather than a long-term growth engine. An economy cannot borrow its way to resilience without expanding its production base.

The shift toward a floating exchange rate, reportedly adopted under IMF conditionality, further complicates the picture. Bangladesh remains structurally dependent on imports—raw materials, fuel, fertilizer, and industrial inputs. When the Taka depreciates against the U.S. dollar, production costs increase almost immediately. These costs are passed down the chain to consumers, intensifying inflationary pressures. Historically, Bangladesh followed a crawling peg system to balance export competitiveness with reserve management. A rapid move toward a floating regime, absent robust domestic production capacity, exposes the economy to external volatility at a delicate time.

The impact is particularly acute because approximately 85 percent of Bangladesh’s workforce operates within the informal sector. When subsidies are reduced, credit becomes more expensive, and imported inputs rise in price, the burden falls first on small producers, agricultural workers, and micro-entrepreneurs. Rising unemployment—formal and informal—combined with declining purchasing power reduces domestic consumption. Slower consumption dampens GDP growth, discourages foreign direct investment, and disrupts supply chains. Stimulus without production capacity merely fuels inflation rather than sustainable development.

Exchange rates are shaped not only by market forces but also by trade balances, capital flows, geopolitical alignments, and multilateral influence. A stronger dollar relative to the Taka increases debt-servicing costs and inflates import bills. In practical terms, Bangladesh absorbs inflationary pressures while the reserve currency economy benefits from strength. As Nobel laureate economist Joseph Stiglitz argued in Globalization and Its Discontents, institutions such as the IMF and the World Bank are not purely technocratic; they operate within political frameworks shaped by global power relations. When the referee designs the rules, defines compliance, and oversees liquidity conditions, the meaning of “victory” becomes ambiguous.

The controversy surrounding efforts to restructure or abolish the National Board of Revenue further underscores institutional uncertainty. Fiscal governance demands predictability and credibility. Abrupt structural experiments, especially under external pressure, risk weakening confidence rather than reinforcing reform.

Meanwhile, concerns persist regarding foreign exchange allocation priorities. Reports of significant dollar expenditures on imported aircraft, agricultural commodities, and other foreign goods raise questions about strategic direction. Without sustained investment in infrastructure, manufacturing ecosystems, and export diversification, Bangladesh cannot compete effectively in global markets. Reducing agricultural and energy subsidies without simultaneously enhancing production efficiency risks deepening structural vulnerability.

A debt-dependent consumer economy often enters a tightening cycle: borrowing leads to currency depreciation; depreciation fuels inflation; inflation erodes purchasing power; weakened demand slows growth; slower growth necessitates further borrowing. Such a cycle undermines economic sovereignty and social stability. The consequences are not abstract—they manifest in higher living costs, reduced employment opportunities, and rising inequality.

Macroeconomic indicators may show temporary stabilization—improved reserves, moderated fiscal balances—but real economic health must be measured at the micro level. Are jobs being created? Is purchasing power stable? Are small businesses surviving? Are agricultural producers competitive? Are education and healthcare investments expanding or shrinking?

The central question is not whether a particular administration is “winning.” The question is whether ordinary citizens are gaining security, opportunity, and stability. Sustainable prosperity requires productive investment, employment generation, strategic industrial policy, and protection for the informal majority. Without these foundations, financial stabilization alone cannot deliver inclusive growth.

Bangladesh stands at a crossroads. It can continue along a path defined by externally conditioned borrowing and consumption-driven adjustment, or it can pursue a production-oriented development strategy rooted in domestic capacity, competitiveness, and long-term economic sovereignty. The decision will shape not just economic statistics, but the lived realities of millions.

Prof. Dr. Arif